History

1797

After the fall of the Republic of Venice, Austria took over its weakened territories, including the navy, its installations, and personnel, which remained largely inactive until the mid-19th century.

This acquisition gave the empire approximately 6,150 km of land borders to secure, most of which, except in Galicia, were naturally well protected. Due to frequent shifts in military-political relations with neighbouring countries and ongoing wars, Austria did not have a permanent border or general fortification system, unlike France.

1814

When Austria took control of the Boka Bay for the second time, it sought to utilise this southeastern part of the Empire strategically. Given the Bay’s critical position on the Adriatic—and, by extension, the Mediterranean—it had long attracted the attention of major powers with competing interests in the region. This made Austria’s task particularly sensitive. As a result, Austria placed great emphasis on the Boka Bay area, investing substantial resources to strengthen its hold. It undertook complex efforts to secure the borders, organise the territory, and prepare for potential attacks from both land and sea. In addition to its military preparations, Austria focused on establishing the infrastructure necessary for sustaining life and work in the region, creating the conditions for a longer-term presence.

The focal point of these efforts, and the ultimate goal of securing the region, was the Otranto Gate or Otranto Strait - a narrow passage between Italy and Albania that connects the Adriatic Sea to the Mediterranean via the Ionian Sea. From a geostrategic perspective, this strait holds immense significance as the principal route for maritime traffic between the Adriatic and the broader Mediterranean. Control over the Otranto Strait enables dominance over the movement of goods and military vessels. Historically, the Otranto Strait has been of critical importance for both military operations and trade routes. During the First and Second World Wars, the Allies and Axis powers fiercely contested control of this passage to secure or block access to the Adriatic Sea.

The proximity of the Otranto Gate, combined with the deeply indented coastline of the Boka Bay, further enhanced the strategic importance of the region.

1840

Trieste and Pula replaced Venice as the primary naval centres, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Austrian, later Austro-Hungarian, Navy was expanding significantly. A new fleet of warships was constructed, elevating the Austrian Navy to the ranks of Europe’s larger naval forces.

Until the mid-19th century, military forces stationed in the Boka Bay (Boka) remained limited. Initially, the existing fortification system was utilised, consisting of old fortified cities and Venetian and Turkish castles, such as those in Herceg Novi, Risan, Perast, Kotor, Budva, and Kastel Lastva, alongside coastal batteries at Rose, Oštra, Luštica, Kumbor, Kamenari, St George, Trojica, and Verige. In the Budva region, apart from the old city of Budva and Lastva, no other inherited fortifications existed.

Over time, a vast and complex fortification system, known as the Naval Port of Kotor / Herceg Novi (Kriegshafen Cattaro / Castelnuovo), was developed across the Boka Bay throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. This system aimed to protect the core of the bay—the naval base and war port—while also controlling routes from the sea to the bay’s interior. In line with this objective, fortifications continued to expand and strengthen under Austrian and Austro-Hungarian rule in Boka (1814–1918), covering new positions, strongholds, defensive lines and zones. This strategic system ultimately encompassed the entire Boka Bay, the Krivošije hinterland, and the Budva-Paštrovići area, extending to the Željeznica River near Bar.

A fortress, by definition, is a fortified structure designed for circular defence to protect personnel and provide a base for offensive operations. Fortresses typically house a permanent garrison and armaments, though their roles, significance, designs, and structures can vary depending on military doctrines, the nature of warfare, and the power and reach of available weaponry. In coastal regions, fortresses were constructed to hinder or prevent attacks on the coast, particularly in areas that served as key access points to inland routes. Though today’s surviving fortifications are often viewed as standalone structures, they were in fact part of an organised, well-designed, and highly functional system—one of the most advanced defence networks of the 19th century. Constructed with cutting-edge technical innovations and strategic military design, the Boka Bay fortress system remains a distinguished example of fortification architecture with significant technical and technological importance.

1838

The first major fortification works were carried out in the Boka Bay, along the border with Montenegro. Three defensive barracks, or forts, were constructed in Paštrovići: Kopac, St Spiridon, and Presjeka.

1839

The Stanjevići Monastery was purchased and converted into a fortress, and a border fortification was built in Brajići.

1853

The second half of the 19th century marked a period of significant social change, reshaping the geostrategic landscape of Europe. In response to these shifts, Austria decided to establish Boka Bay as a naval base in 1853.

1850-

1854

Under the leadership of Lazar Mamula (1795–1878), an Austrian baron, artillery general of the Austrian Empire, and governor of Dalmatia, the first line of defence was established through the construction of the forts Oštro, Mamula, and Arza.

1855

A smaller fortification and a gendarmerie-customs station were constructed at Crkvice.

1860–

1863

The development of a new weapon—rifled artillery—greatly increased the range and destructive power of such armaments, rendering the fortresses of the first defence line obsolete. This advancement introduced new requirements for the organisation of defence. As a result, the fortifications in Boka Bay constructed in subsequent years were designed to be lower, with casemate vaults of greater thickness, and increasingly entrenched within the terrain. This shift is exemplified by the group of fortifications at Luštica, Kobila, Grabovac, Goražda, and Vrmac

1873

Rifled cannons with calibres of 179 mm and 210 mm were introduced into the Austro-Hungarian arsenal.

1875

This period marked a shift in defence strategy, with mortars (Mörser) deployed on open platforms for combating enemy ships. Close defence relied on flanking guns housed in casemates, which were protected by walls up to two metres thick.

1880

Since the initial mortars proved heavy and challenging to manoeuvre, they were replaced by cannons with calibres of 90, 150, and 210 mm. In 1898, even more powerful mortars with a calibre of 240 mm were introduced.

Od 1814. do 1882. godine Boka Kotorska je imala status tzv. primorske zaprečne tvrđave.

Na prelazu u 20. vijek, stavovi Austrougarske prema vojno-strategijskoj ulozi Boke Kotorske ponovo su se izmijenili. U tom je periodu oko zaliva izgrađen veći broj isturenih, samostalnih fortifikacija, koje su formirale jake odbrambene pojaseve. Tako je postojeća zaprečna tvrđava vremenom prerastala u primorsku pojasnu tvrđavu.

1890

The main defence of the Boka Bay was shifted to the Kobila–Kabala line. Between 1895 and 1897, a series of forts and batteries were constructed in the Luštica–Kabala–Kobila area. Forts were established at Luštica and Kabala, along with the Klinci battery, and flanking and torpedo batteries at Rose. At Cape Kobila, forts Kobila Upper and Kobila Lower, the flanking battery Kobila, the torpedo battery Kobila, and the Košare battery were constructed, along with several artillery positions and auxiliary facilities for defending against vessels attempting to enter the Herceg Novi Bay. A third line of defence was also organised, utilising old Austro-Hungarian positions in Rose and Pristan, the battery at Kumbor, the fortified belt around Herceg Novi, and the renovated, mortar-reinforced fort Španjola.

1914

At the start of the First World War, the Boka Bay was one of only three fortresses within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy equipped with three layers of defensive belts.

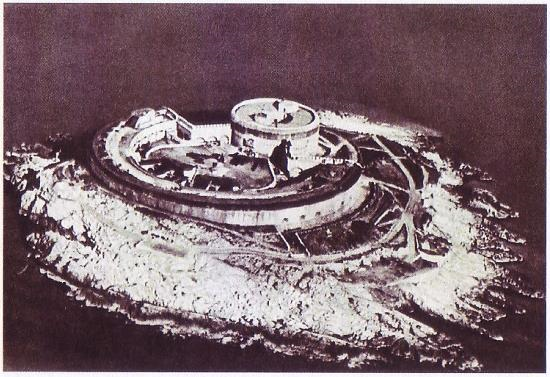

The Mamula Fortress was constructed as a circular, multi-storey tower with flanking guns in casemates and two casemate batteries (one on the east and one on the west), each holding six guns. However, with the development of new weaponry—primarily rifled cannons (1858–1863) and explosive shells—the fortress’s armament quickly became outdated. Its high but inadequately thick walls lost their defensive function, rendering the fortress almost unusable for its original purpose a mere decade after construction. To modernise the Mamula Fortress and adapt it to newer weaponry, significant modifications were made in 1875 with the addition of a Mörser battery on the southern side, between the central courtyard and the outer rampart. This battery included positions for four 210 mm cannons, an ammunition storage room, and an armoured central observation post, extending the cannon range at sea to 10.5 km and effectively restoring the fortress’s operational capacity. Initially, the fortress housed around 40 cannons of varying calibres. By 1914, at the onset of the First World War, Mamula was equipped with four 210 mm M-1873 mortars, eight 80 mm M-95 cannons, and ten 80 mm M-75/96 cannons. It was also outfitted with a searchlight. During the First World War, the French fleet entered Adriatic waters on nine occasions, briefly patrolling the region. On three of these occasions, they launched attacks on the fortifications at the entrance to the Boka Bay. The first attack occurred on 1 September 1914, at 7:30 a.m., when Admiral Auguste Boué de Lapeyrère’s fleet opened fire on Mamula from a distance of 13,000 metres. The assault involved ten 305 mm shells per cannon and lasted for 15 minutes. Despite this bombardment, the Mamula fort sustained no significant damage, and its guns did not return fire as the French ships remained out of range. This initial assault was the only planned attack on the Boka Bay’s entrance forts; the subsequent two attacks were unplanned.

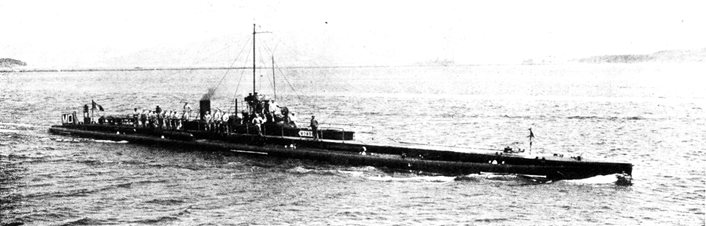

The second attack on the Boka Bay’s defences occurred on 19 September 1914, led by Rear Admiral Senès’s reinforced Second Light Division of Ships. Due to heavy fog, the French ships inadvertently approached the coast to within 5,000 metres, allowing the fortress crew to spot and open fire. The ships were targeted by 150 mm cannons from Luštica, with a range of 10.5 km, and by 210 mm mortars from Cape Oštro, though Mamula’s guns had no effect. When the French ships returned fire, they struck Fort Mamula from 5,000 metres. A 305 mm shell hit the breastworks, penetrating 12 metres of wall and soil before exploding in the soldiers’ kitchen and damaging the circular tower. Another shell destroyed part of the rampart. All three forts—Mamula, Arza, and Oštro—were impacted, resulting in one sailor killed and two wounded. The third and final attack on the fortifications occurred on 17 October 1914. This time, Mamula was not targeted, marking the last instance of a warship attacking the fortresses at the entrance to the Boka Bay. On 14 January 1915, the French submarine Monge approached the entrance to the Boka Bay and remained there for two days. According to its commander, the submarine reached as close as 800 metres to the Oštro-Mamula line before it was spotted and fired upon by guns from both Mamula and Punta Oštro.

Later, on 29 December 1915, Monge, under Commander Roland Morillot, was patrolling near the bay entrance when it was spotted and sunk by the Austro-Hungarian destroyer Helgoland.

During the First World War, Mamula Fortress was briefly used as a prison for sailors who had initiated a mutiny, inspired by the October Revolution. In addition to the sailors, local citizens from Boka were also imprisoned on the island, including Mirko Komnenović, the mayor and a prominent historical figure of Herceg Novi.

1918

Following the capitulation of Austria-Hungary, the empire permanently withdrew from the Boka Bay, marking the beginning of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. During this period, Mamula Fortress continued to serve as a military facility, though no notable military actions were recorded. Evidence of its use includes the names of soldiers carved into the stone.

1941

6 April – The Kingdom of Italy attacked Yugoslavia, initiating the April War, which ended in Yugoslavia’s capitulation after 11 days. Italy then occupied parts of Slovenia, the entire eastern Adriatic coast, Herzegovina, Montenegro, Metohija, Kosovo, and sections of Macedonia.

13.07.

13 July – An uprising began in Montenegro against the occupying forces, soon gaining widespread popular support.

15.08.

The uprising was suppressed, and the entire territory of Montenegro came under Italian military control.

03.10.

The Italian Military Governorate, with headquarters in Cetinje, was established as the main authority in Montenegro.

In occupied Boka Bay, the Kingdom of Italy implemented a system of prisons and camps with strict internal regimes. One of the most notorious was located in Kotor, in the former Austro-Hungarian prison building in the Old Town. Despite the harsh occupation and repression, the communist movement grew stronger and gained more support.

1942

30 March – The Mamula concentration camp was established, becoming part of the Italian network of prisons and camps.

1943

Eighteen months after its establishment, the last prisoners left Mamula on 30 September 1943.

1944

With the end of German occupation, Montenegro’s territory was liberated by the Partisan forces, marking the conclusion of military operations in the country.

1945–

2015

After the war, Lastavica Island and the Mamula Fortress were abandoned, gradually falling into disrepair over the following decades